In photo: German Landsknechts

The next three weeks were a constant crescendo of tension. The armies faced each other in daily skirmishes, night raids and small battles, without either side being able to prevail. Charles V’s troops obtained small local victories without ever managing to break through the French positions, which were strong and well defended. Despite attempts to dislodge Francis I’s army, the French continued to maintain their defensive superiority.

Charles V’s commanders inside the walls are facing serious difficulties due to the lack of money to pay the Landsknechts, who are threatening to abandon the army. Antonio de Leyva, commander of the imperial forces, is insistently demanding decisive action. The war can no longer continue under these conditions: food supplies in the fortified city are rapidly decreasing and the situation is becoming unsustainable.

The Imperial Attack

Driven by necessity, the imperial commanders decide to go for broke. After having discarded the idea of a frontal assault, the Marquis of Pescara devises a bold plan: to move at night and penetrate the Visconti Park to occupy Mirabello, with the intent of entering behind the French and cutting off their communications with Milan, forcing them to fight in the open field and in unfavorable conditions.

During the night between February 23 and 24, the imperial troops set out, feigning a retreat. While the bulk of the troops headed towards Lardirago, some groups of light infantry covered the operation with distracting noises and a few arquebus shots to distract the attention of the French.

After a few kilometers, the imperial army approaches the wall of the Park, near Due Porte, where the Spanish sappers are already at work to open breaches in the wall of the Visconti Park and allow passage. The work, long and tiring, ends at dawn, and the vanguard led by Alfonso d’Avalos, composed of about 3,000 arquebusiers, manages to penetrate the park, covered by the fog and the poor light of the morning, to head towards the French headquarters.

The French, distracted by diversionary maneuvers, do not immediately realize the danger. Del Vasto’s arquebusiers reach the castle of Mirabello, catching the few French soldiers on guard and the crowd of civilians nearby by surprise. Surprised in their sleep, many do not have time to flee and are massacred by the imperial soldiers who sack everything. Del Vasto immediately restores order and takes up position around the castle. In the meantime, the bulk of the imperial army enters the Park, heading towards the castle of Mirabello.

In photo: Francis I and his knights,

Flemish tapestries of the Battle of Pavia, 16th century, detail of the second tapestry, Museum and Royal Wood of Capodimonte, Naples

The French reaction

The alarm is raised in the French camp. Francis I and his commanders immediately understand that the situation is serious. It is no longer a simple night raid, but a decisive action by the imperials. Tensions are skyrocketing.

The French quickly organized themselves: the king, with about 800 gendarmes and their entourage, positioned themselves on the left, along the Vernavola. In the center, 3,000 Swiss soldiers formed a square, while on the right the Banda Nera, composed of 4,000 lansquenets, occupied the wing. Fourteen cannons were placed along the battle line, while a reserve of 400 gendarmes, under the command of Charles of Alençon, prepared to intervene if necessary. The Italians of Giovanni de’ Medici’s bands, absent because wounded, were to cover the area north of Pavia to prevent a possible sortie of the besieged. Another 5,000 Swiss deployed to the south, as well as several thousand French and Italian soldiers camped beyond the Ticino, were too far away to take part in the battle.

While the French army prepares for battle, the imperial army marches in compact formation: cavalry on the right, a strong contingent of 5,000 Spanish infantry in the center and two huge squares of lansquenets on the left with 6,000 men each. The Marquis del Vasto, fearing to be isolated, has in the meantime abandoned his position at Mirabello and rejoined the main army with his 3,000 arquebusiers.

As the armies approach, battle becomes inevitable. The French artillery begins to bombard the imperial squares, the first shots opening furrows between the imperial squares. To protect themselves, the infantrymen lie down on the ground, taking shelter in the natural depressions of the terrain. Meanwhile, Francis I, eager to finally enter into action, wastes no time and decides to launch an attack followed by his knights, thus losing all contact with the rest of the army.

The French charge manages to temporarily repel the imperial one, the French stop to let their horses rest, exhausted by the fight. Francis I is delighted, but the real twist comes right at that moment.

Defeat and capture of Francis I

The Imperials are in a critical situation.

Their cavalry has been repulsed, the infantry runs the risk of being attacked frontally by the enemy and at the same time of being taken from behind and on the flank by the French Gendarmerie.

With a clever maneuver, the Marquis of Pescara decides to move the imperial arquebusiers to the extreme right, aiming directly at the French cavalry.

The knights, unprotected, begin to fall under the close fire of the arquebusiers, many dragged to the ground by the fall of their steeds.

With a rain of lead, the French gendarmes are decimated.

The imperial cavalry, which has meanwhile reorganized, joins the fight.

Meanwhile, the fortunes of the battle are turning in favor of the imperials also in the center and on the left, where the imperial lansquenet squares are getting the better of the French.

The Black Band, though fighting bravely, is overwhelmed by the superior forces of the Imperials and almost all of its members fall in the fray.

The Swiss, who had held out until then, began to give in and were put to flight.

Francis I, shocked by the direction the battle was taking, first tried to resist surrounded by a small group of knights, and then to flee but was unable to escape. Having reached the Repentita farmhouse, a shot from an arquebus unseats him and he falls to the ground, his horse falls dead on top of him. Three Spanish knights take him prisoner.

Shortly after, the king was brought before Charles de Lannoy, the viceroy of Naples, who formally received the surrender of the French sovereign.

Meanwhile, the Duke of Alençon, who saw the battle turning against the French, rather than intervening to help Francis I, decided to retreat and crossed the Ticino on the pontoon bridge thrown by the French during the siege, abandoning the battlefield.

The defeat is total.

The Swiss, now in retreat and attacked by Antonio de Leyva’s soldiers who had defeated Giovanni de Medici’s few Italian soldiers in a few minutes, sought refuge by heading towards the Ticino and the pontoon bridge already used by Alençon.

But a horrible surprise awaits them: after crossing the river, he had the bridge cut down.

Pursued by the Spanish light cavalry who gave no respite, the Swiss threw themselves into the river where many of them drowned, swept away by the strong current.

The Imperial Triumph

The Battle of Pavia, which lasted less than two hours, ended with a crushing victory for Charles V. The capture of the King of France was a devastating blow, not only for the outcome of the battle, but also for the entire war. The French defeat was total: between 7,000 and 8,000 soldiers lost their lives, while thousands of prisoners were taken.

Imperial losses are around 500 men.

The Battle of Pavia marks a turning point in European history, not only for the imperial victory and the capture of Francis I, but also for the symbolic implications it carries: the French noble chivalry, with its pride and tradition, is annihilated not by enemy cavalry forces but by humble soldiers armed with arquebuses, the hated firearms that change the face of war forever.

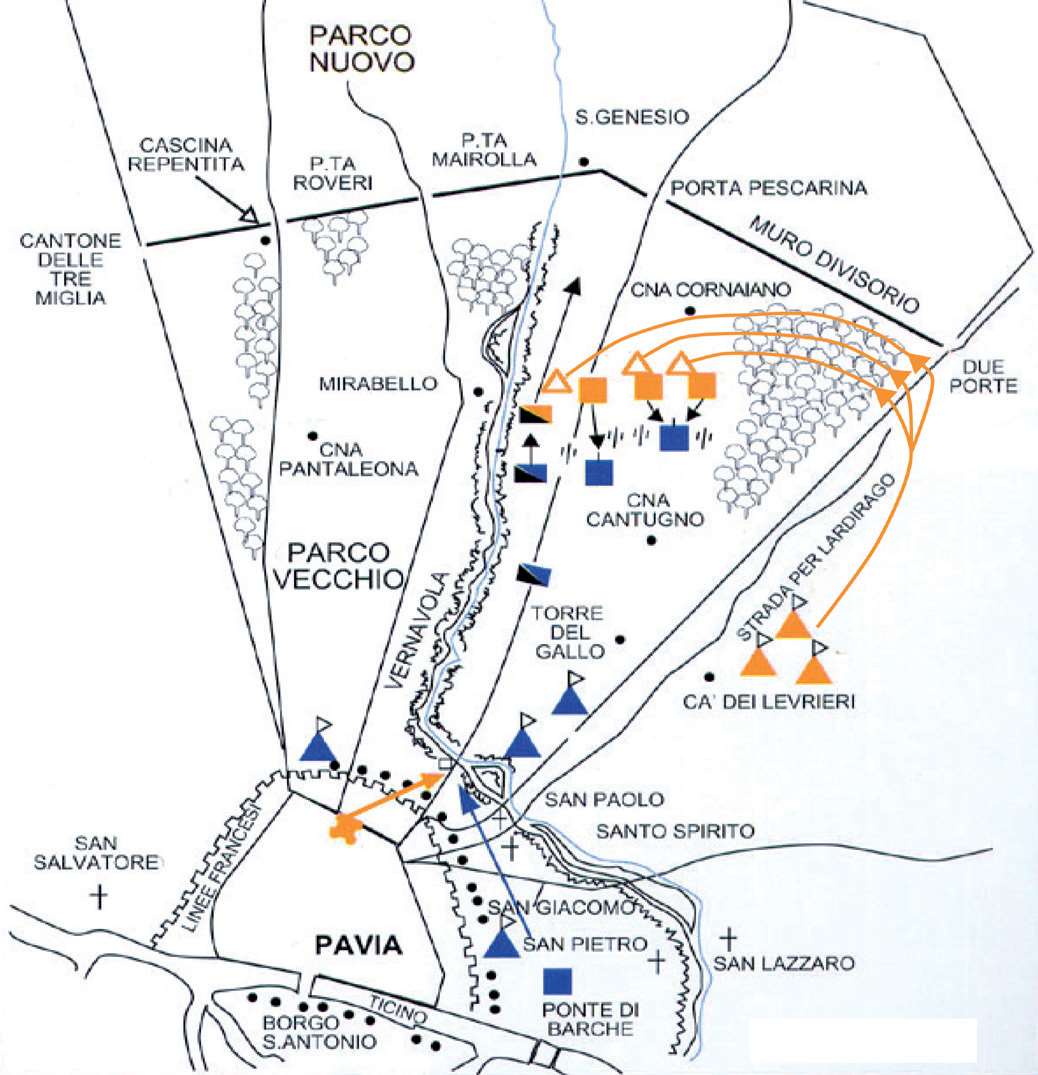

In photo: Map of the Battle of Pavia: in blue the French, in yellow the Imperials

In the photo: The bridge over the Ticino,

Flemish tapestries of the Battle of Pavia, 15th century

XVI, detail of the sixth tapestry, Naples, Capodimonte Museum

In the photo: Ferdinando Francesco d’Avalos, Marquis of Pescara (1489 – 1525). From a noble Spanish family transplanted to Italy, he was the best imperial captain during the Italian Wars.

In 1525 he was the architect of the imperial victory of Pavia.

He died that same year as a result of wounds sustained in that battle.

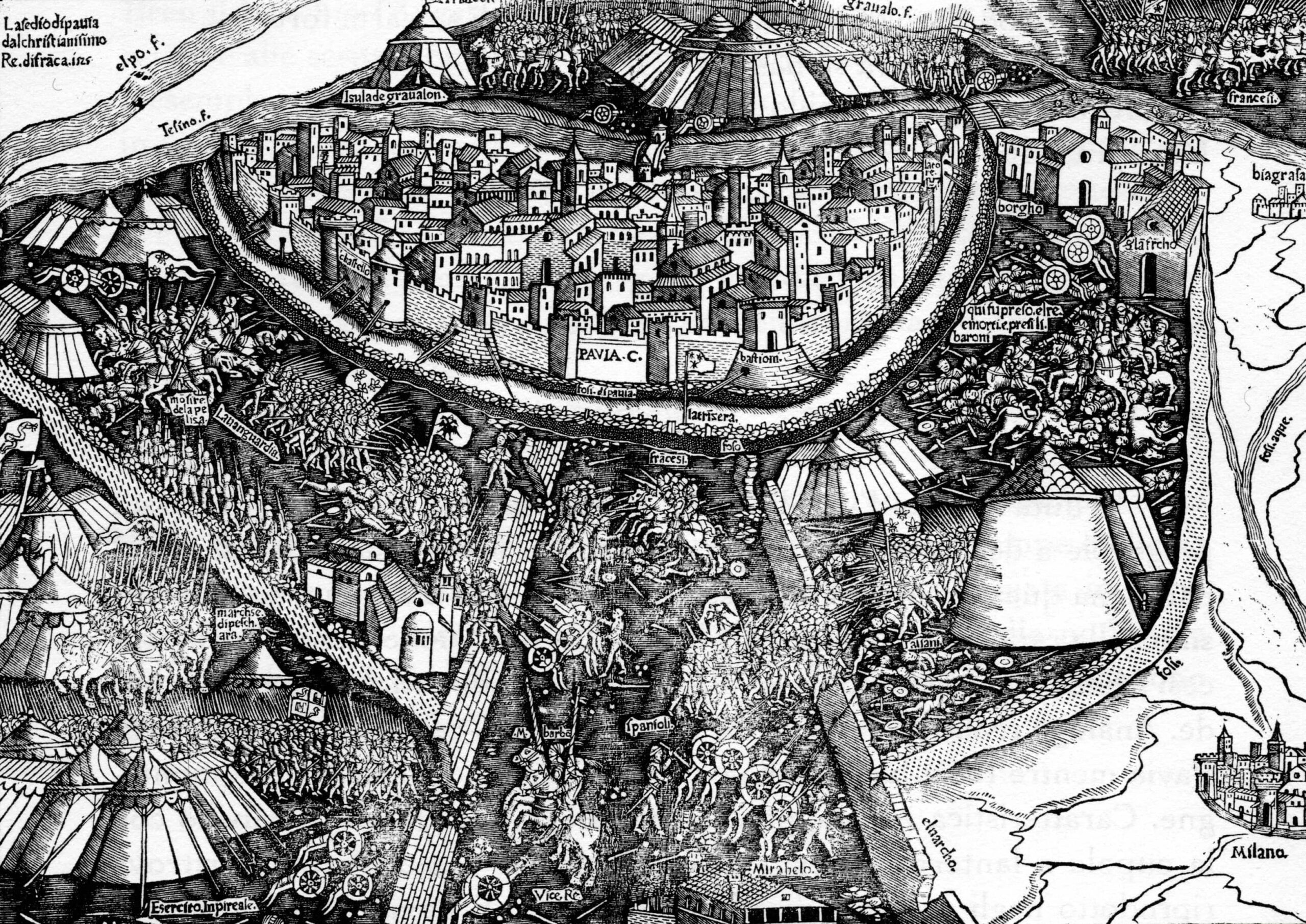

In the photo: The Battle of Pavia in the print by Giovanni Andrea Vavassori known as Guadagnino (attributed).

Pavia, Civic Museums.